How women won their place in rail

At SNCF, we’ve been promoting gender diversity and equality in the workplace for several decades. Today women account for 20% of our workforce. Learn how professions in the rail industry slowly opened up to them.

Keeping step with societal change

In 1886—before SNCF’s time—just 7.4% of railway employees were women. Today, over a century and a half later, women hold positions across all sectors and at every level of the corporate hierarchy. Dive into the history of women in rail to see just how far they’ve come.

A threat to public decency…

Work outside the home was frowned on for women in the 19th century: male workers feared competition, while middle-class women sought an identity as homemakers and educators. Nor was it deemed appropriate to mix men and women in the same premises. Social mores were strict and gender segregation the norm.

But as railroads expanded, demand for labour grew. The very first women employed by rail companies were destitute widows of rail workers. Managers offered them paid employment—albeit not entirely out of compassion, since they earned substantially less than their male counterparts.

The first female jobs: level crossing guards

The most iconic positions open to women were as crossing guards. Initially, candidates were the wives of the track and crossing workers charged with maintaining each site. The job? Lowering gates to keep vehicles from crossing as trains approached, and lifting them once passage was safe. Portrayals of women crossing guards in popular films and novels have enshrined them in railway history.

The Industrial Revolution—a godsend

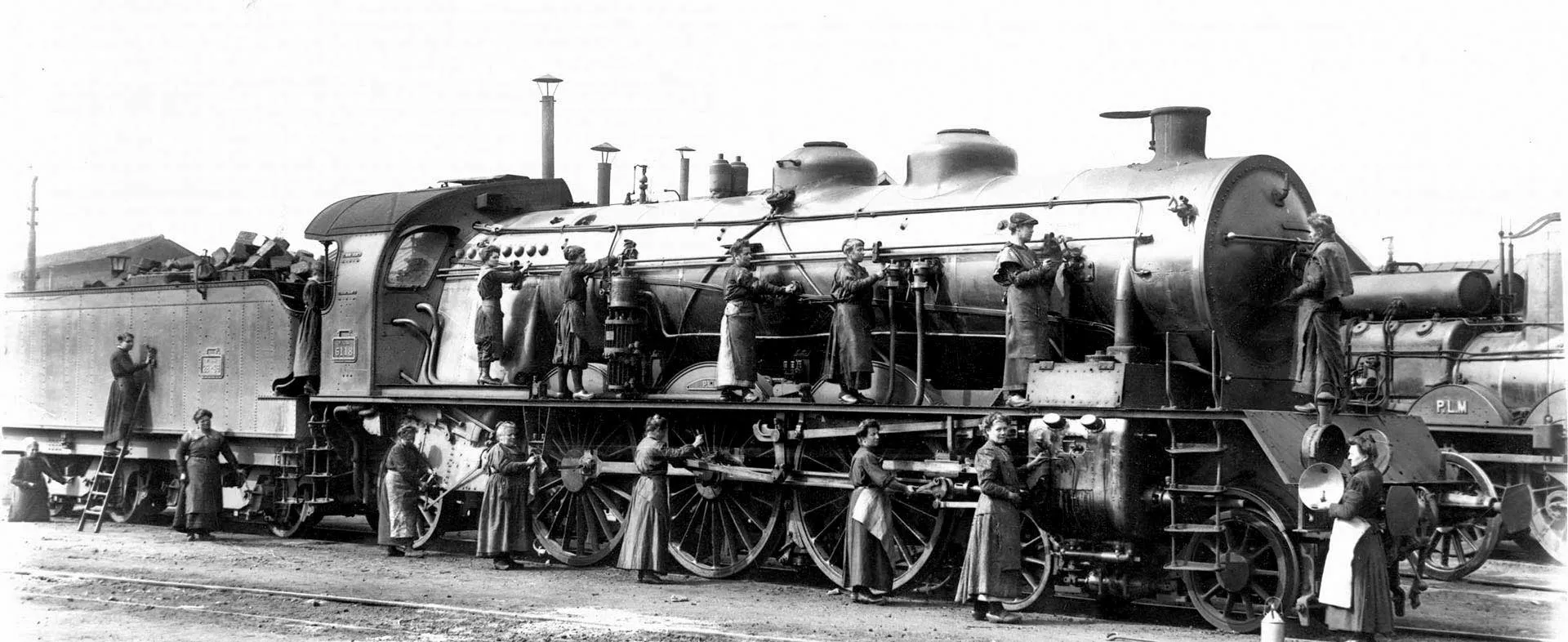

As women began working for rail companies, employers discovered what excellent value for money they offered—women were efficient and hardworking, didn’t drink on the job, and were just as strong as men. Yet despite a surge in female employees, most were hired as cleaners or in clerical positions, as cashiers and office workers. They were also ticket collectors, issuing and tallying up ticket sales, and bookkeepers. Or news agents, selling books and newspapers to travellers.

War brings change

The two world wars drew men out of the workforce, spurring a fresh surge in female hires. To be sure, women returned home once the fighting ended and soldiers came back from the front. But their contribution shifted mentalities and paved the way for greater acceptance of female workers.

In the wake of World War II, both women and politicians were primed for serious change. At long last, France’s Constitution of 27 October 1946 guaranteed women equal rights with men. Then, with the right to vote, women acquired a new civil and political status. Yet it was not until the early 1960s that female employment skyrocketed.

Continuing the fight against inequality

At SNCF, core railway jobs—in traction, operations, maintenance and signalling, but also senior management—opened up to women towards the end of the 20th century. Yet even today, the percentage of women employees masks real disparities: women are over-represented in sales and cross-functional positions, but continue to punch below their weight in train driving and SUGE rail security services.

Enter SNCF Mixité

The SNCF Mixité network was set up in 2012 to promote gender equality in the workplace and encourage the hiring of women in technical fields typically dominated by men. As France’s first corporate women’s network, it had attracted 7,500 members by 2019. In June that same year, representatives set off around the country to meet SNCF employees aboard a specially outfitted train as part of a traveling exhibition to promote gender parity and combat sexism.

Women rail pioneers

Across these decades, at SNCF we’ve had many a pioneering woman get her foot in the door, pave the way for others, and break the glass ceiling to reach positions at the very top. While most are relatively unknown, others are now an indelible part of our rail Group’s history. They include:

Blanche Le Thessier, SNCF’s first female senior manager

Born in 1897, Blanche graduated from Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, France’s prestigious engineering school, after obtaining undergraduate degrees in science and law. When she retired in 1953, she was Chief Engineer of the coach and wagon research division, and the only woman to serve as a senior civil servant at SNCF.

Sylvie Guedeville, first female TGV driver

In 1976, French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing signed a decree authorizing women to do shift work. In 1983, Sylvie Guedeville became one of the first two women to work as deputy drivers. And in 2004, she was promoted to first woman driver of a high-speed TGV trainset.

Mireille Faugère, first female manager of a major railway station in France

In 1991, Mireille Faugère was named manager of Paris-Montparnasse station, the first woman to hold this position. She was also the driving force behind Voyages-sncf.com, launched in June 2000, which became one of France’s leading e-commerce sites in just a few months.

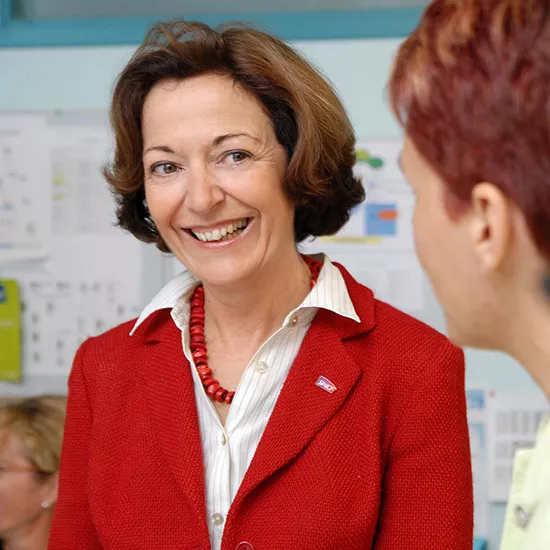

Anne-Marie Idrac, first chairwoman of SNCF

In 2006, Anne-Marie Idrac became SNCF’s first chairwoman and the first vice-chairwoman of the International Union of Railways (UIC). Milestones during her term of office included the reform of French railway workers’ sector-specific pension plan and the introduction of minimum service requirements.

Share the article